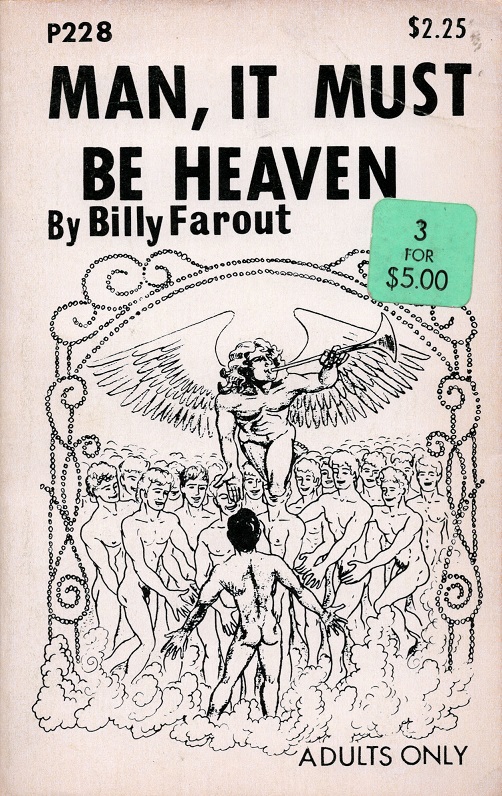

Gay afterlife meets John Lennon utopia in this fantastical pulp novel. Murder, vengeful ghosts and tongue-in-cheek religious commentary are thrown in for good measure. As a literary artifact it offers a delightfully campy lens into the fantasies and fears of queer existence during the early 1970s.

The novel opens with Reggie Poppov waking up in the “Gay Wing of Purgatory.” He’s disoriented and wearing a big poofy wedding dress. Leaning over him is a “half nude angel” whose rippling physique makes him “more handsome” than Michelangelo’s David. The angel asks what happened to him. Reggie gradually recalls that he had dressed in wedding drag so he could legally marry his boyfriend, Bob. While posing for pictures on the Golden Gate Bridge, however, Bob pushed him over the edge so he could inherit Reggie’s family fortune.

Reggie is bummed to realize that his lover had murdered him, but the hunky men of Purgatory help him forget his troubles. He enjoys intimacy with such figures as Roman soldiers and Greeks with god-like bodies. There’s also Schwartz, the statuesque angel who’s been so helpful with navigating his new existence.

But the more Schwartz shows off this city in the sky, the more suspicious Reggie becomes. The angel acts like this is Heaven, yet operations are far from perfect. Sorrow is abundant in such places as a celestial gay bar where guys avoid eye contact and talk to each other “every couple of years”—and only then to “ask what time it is” or if anyone has a match.

Beyond the gay bar are other private rooms called “Quarreling Lovers,” “Whip City” and “Broken Hearts.” Reggie peers into Broken Hearts and finds gay men bemoaning “O woe is me. I loved you so, and you broke my heart, but it was my fault . . . “

“Are they suffering?” Reggie asks his angel guide over the room’s dreary harp music.

“They love to suffer,” Schwartz explains.

Reggie is reminded of his earthly peers who did seem to love being depressed, but it doesn’t seem right for them to go on this way in perpetuity. Is he destined for one of these rooms? Who’s in charge of this place anyway? He confronts his angel for answers.

Schwartz, with his New York accent, confesses that leadership in the afterlife is poor and those in charge are really just playing mind games:

They try and let you think they got control. But they don’t got control. Truth is, nobody got control. Just whoever tells you he’s got control and you believes him, then he’s got control. It works like that all the way up to the top. And the Biggest Boss of all, well, he retired years ago when they tried to turn this place into a mail order service, and the truth of the matter is, nobody knows what’s going on. (p. 48)

Despite this lack of confidence, Schwartz suggests Reggie follow protocol and visit the current “Big Cheese” to find out where he’ll be assigned.

Reggie proceeds through a cruelly-slow DMV-like waiting area before finally meeting with Mr. “B.C.” When Reggie points out the problems with Purgatory, Big Cheese laughs and reveals that those rooms are actually Hell. This makes sense to Reggie, as he realizes the rooms are just an exaggeration of the unpleasantries on Earth.

Reggie is not destined for Hell, however. There’s a clause that anyone who is murdered gets a free pass to Heaven. But because Reggie, son of a wealthy film actress, had too easy of a life he is not yet ready to proceed to glory. To remedy this, the Big Cheese decides to “reinstate” him back to the world of the living, this time in Italy.

It’s not immediately clear how being sent to a romantic locale will be a form of atonement, but context clues reveal the narrative is interacting with stereotypes about gay Italians.

“Oh no, not [Italy!]” cries Reggie, recalling from experience the “obscure and exasperating sexual customs that permeated the country where the Catholic church had been founded.” As will be seen, these “customs” seem to revolve around internalized homophobia. Reggie recalls how Italians tend to seek out brief one-sided homosexual encounters, but their religious guilt prevents them from offering any reciprocation or long-term commitment.

Despite Reggie’s protestations, the ruling is final.

“Your soul needs a trial, a chance to fail,” says Big Cheese. “You must learn humility. You must do battle with morality and fail, FAIL do you understand, before you can enter the Kingdom of Heaven.”

So Reggie is beamed down to Italy with only a fuzzy memory of his afterlife experience and barely enough lire to get by. Soon enough he indeed finds himself mixed up with frustrating sexual encounters where he puts forth his best effort but receives no pleasure in return. After a number of such “failures” the B.C. possibly feels sorry for him because he then develops supernatural powers. He discovers that salt water makes him invisible and, with a running leap, he can fly.

In Venice, Reggie uses his invisibility to sneakily join two gondoliers. It’s late and as they dock their gondola for the night, Reggie manages to give them both an invisible blow job before they become suspicious.

“Maybe it’s the fog or something,” suggests one gondolier as explanation for their otherworldly penis pleasure.

Reggie decides to have some fun. Using his “most bizarre and ghost-like voice,” he moans “I am the faggot of the mist. I sucked your cocks…”

The gondoliers jump overboard in terror, leaving Reggie alone once again.

Reggie enjoys his powers for a time but is soon arrested. Ironically this is not for illegally flying over Rome, sexual assault or breaking into houses, but because the police mistake him for a guy who’s been distributing LSD. Reggie is furious at the false accusation, but with the Italian legal system there’s nothing he can do but wait out his sentence in jail.

Actually, there is something he can do. His cellmate, Ignazio, is a “short stocky tough looking guy with a small mustache” who disproves Italian stereotypes by being a generous lover. Perhaps too generous. His impressive equipment is a delight at first, but physically damaging after repeated use. Then there is his temper to worry about.

On the rare courtyard excursion, Reggie’s lover watches over him with severe jealousy. Anyone who dares to “make contact with Reggie’s eyes” faces the vengeance of a “growling…madman” who is not opposed to murder to ward off threats of competition.

Abused and depressed in his cell with Ignazio, Reggie regains full memory of all that happened in the afterlife and devises a plan to return to Purgatory. He taunts Ignazio, lying that he’s been unfaithful and saying he doesn’t love him any more. His goal is to infuriate Ignazio so much that he will murder him. Then Reggie can show the Big Cheese he learned hardship and move on to Heaven.

Finally the day arrives when Ignazio is worked up enough to push Reggie over the long drop to the courtyard below. Mirroring his deadly fall off the Golden Gate Bridge, Reggie once again plummets to his death.

Reggie wakes up in the Gay Wing of Purgatory. Again. As before, Schwartz is there to greet him. Reggie tells him his new theory that the Big Cheese is really a bad guy, and there’s no telling who else might be corrupt with him.

As if on cue, another deity appears. This time it’s the “Trick Goddess” whose special talent is creating disaster in the lives of gay men. “I get things together and I fuck things up,” she explains, “Just. For. Fun!” She speaks in the “deep voice of a female impersonator” and laughs “like Talullah Bankhead” while holding her long pink cigarette.

Reggie is not intimidated by her power and gives her a piece of his mind: “What should it matter to you if Jack Shit is happy or sad. Let him get who he needs. It’s bad enough down there without you stepping in to fuck things up for us.”

The Trick Goddess is taken aback and the narrator reveals that she hasn’t been put in her place like that since “Oscar Wilde had pulled her hair for being thrown in an English prison.”

The two argue for a time before finding something they can both agree on: Bob, Reggie’s murderous husband, needs to be taught a lesson. The Trick Goddess sends Reggie back to earth as a ghost so he can haunt his ex-lover.

In the luxury of his inherited estate, Bob is romantically involved with a new man. Reggie ruins the party by moving a framed picture of himself to various locations about the house. Since he’s an invisible ghost, all Bob sees is the hovering picture. Frightened into frenzy, Bob blindly runs up the big staircase and accidentally falls over the bannister to his death.

After Bob dies, Reggie floats back up to Purgatory. A lot happened while he was busy haunting. Inspired by Reggie’s rebellious attitude, Schwartz was imprisoned after he dared to ask the Big Cheese for a vacation. Horrified, Reggie reflects on afterlife politics and plans his next move:

The meek, they say, shall inherit the earth, but what about Heaven. It is the bold, the crooks and bank presidents that take over in Cloud City. And the only reason they have power is that arriving souls still believe in their power. Nobody wants to rock a boat. And LeRoy Schwartz had rocked the boat. Reggie had to find him and help him NOW! (p. 136)

Reggie locates his beloved Angel in a dark, grim prison. Schwartz is “screaming horribly” and surrounding him are “big black spiders…climbing up his tied legs, and dangling from little webs in front of his terrified face.”

Following his logic about the afterlife being ruled by belief, and clearly inspired by John Lennon’s 1971 classic tune “Imagine,” Reggie announces “I don’t believe in spiders!!!” and “I don’t believe in prisons in Heaven!” Miraculously, these things vanish as soon as he imagines them to be gone.

While making their escape, Reggie frees other prisoners along the way. These angels take up protest signs proclaiming “Freedom and equality for angels” and “Heaven Now” as they march on to confront the Big Cheese.

Reggie doesn’t follow them and instead tells Schwartz “I can imagine even a better place than this…if you’re willing, I’d like to take you there with me.”

Schwartz says that sounds wonderful. The two fly up to a big fluffy pink cloud that is “above” Heaven. Reggie announces “I don’t believe in bureaucracy!” and suddenly whole cities of clouds disappear below them. “The Trick Goddess is a dirty bitch!” he screams, and there is a small poof of smoke.

Then, channeling John Lennon once again, Reggie takes Schwartz in his arms and says “I can imagine a place where there is nothing but peace, can’t you!”

Schwartz is skeptical: “I’ve been hearing that word ‘peace,’ and everybody is looking for ‘peace’ and it seems like there ain’t nobody who ever finds it.”

“We’re finding it,” says Reggie. “Look at that rainbow…just beyond that rainbow is peace.”

“Let’s go there together,” says Schwartz. They share a kiss and slowly drift into what comes across as a non-religious form of death. Their pink cloud passes through the “grand arch of the big rainbow into eternity” and then the two lovers fall into a “warm, comfortable, peaceful, tranquil, enduring sleep, sleep, sleep, sleep, sleep, sleep, sleep, sleep, sleep.”

And that’s how it ends. For a slim paperback that’s probably 69% sex scenes, there’s a lot to unpack. Gay pulp fiction frequently interacts with the gay liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s, but few take on religion with such unambiguous allegory. Of course, religious institutions have long been the antagonist of equal rights for the LGBT+ community. Rather than go after Bible-beaters, however, this novel targets the very premise of Heaven and Hell.

John Lennon’s “Imagine” was actively flooding the airwaves when this book was written and there is little doubt that the song’s first lyric, “Imagine there’s no Heaven,” was a major source of inspiration. The final image of Reggie and Schwartz embracing each other before fading away into rainbow light is a far more tranquil conclusion to life than navigating the eternal complexities of afterlife “bureaucracy.” Can there even be a “Heaven” if it is so obnoxious to live there? How long before it turns to spiders and looks more like Hell?

The message seems to be that organized religion is not organized at all, but rather a bunch of nonsense rules made to “control” anyone unfortunate enough to believe. Yet as powerful as these entities are, they are easily conquered as soon as one simply stops believing. Part of the brilliance of Lennon’s iconic song, and its implementation into this novel, is recognizing that the concept of Heaven is actually laden with anxiety. It’s supposed to be this magical place full of happiness, yet not buying into it is the real source of peace.

For Reggie and Schwartz, ascending into gay rainbow sleep is the glorious afterlife actually worth imagining. In an unlikely coincidence, “Sleep” is repeated nine times at the end. This is a plausible nod to numerology which believes nine signifies “the finality of one cycle and another’s possible beginning.” Let life conclude, Billy Farout seems to argue. Then, if there is a beyond, let it be the start of something new.

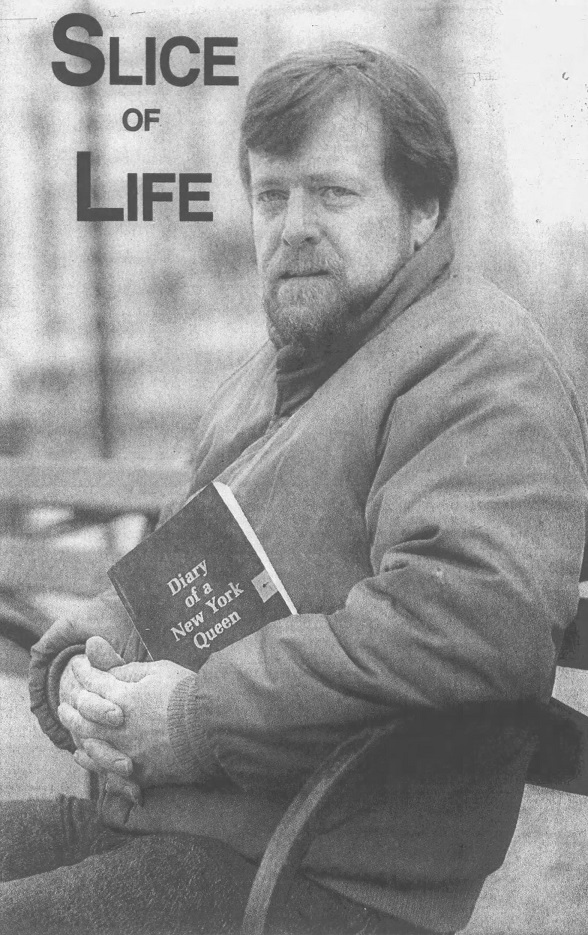

Who was Billy Farout (“far out!”) anyway? Well, it’s the groovy pseudonym of William Edward Barber (1946-1992). William had personal experience with Italians having studied writing in Perugia, Italy. He was also a professor of English and Creative Writing at Wilkes University in Pennsylvania. He was born in Pittston, PA but his family moved up and down the east coast before ending up in California. “I was in San Francisco State when the riots (in the late ’60s) and everything came down,” he recalled in one interview.

Being so close to activism likely inspired such scenes as the rebellious angels demanding justice in Man, It Must Be Heaven and characters in his other novels. He was amazed at how popular his “porno” novels were, recalling a visit to 42nd street in New York where a store sign read “We have all the Billy Farout books!”

Later he had modest success with his novel Diary of a New York Queen (1988) which he says was a gay adaptation of Dorothy Parker’s “Diary of a New York Lady” (1933). To write an authentic-sounding effeminate queen character, Barber conducted extensive research. Though gay himself, he said he was generally a guy-guy who smoked “unfiltered Pall Malls” and wore plain blue sweaters with comfortable jeans. So he would ask bartenders to direct him to the nearest “mincing-type gay” so he could “interview” them.

The research apparently worked. Though published with a small press, Diary of a New York Queen was an instant sell-out in his home town and in major cities like Los Angeles, Chicago and New York.

Though probably incomplete, here is a list of William Barber’s confirmed works:

as Billy Farout

–Fresh from the Farm (1972)

–Hero in the Bedroom (1972)

–A Sailor Coming Out (1972)

–The Chauffeur Did It (1972) (this is actually Book One of the Reggie Poppov saga, focusing on his relationship with boyfriend Bob and leading up to the push off Golden Gate Bridge)

–Man, It Must Be Heaven (also referred to as Men! It Must Be Heaven) (1972)

as William Barber

–Abyss: A Collection of Poems 1973-1974 (1974)

–Get Over It: Eight Sonnets (1975)

–Diary of a New York Queen (1988)

William passed away at the young age of forty-six. His poetry has perhaps become his most enduring literary works, having been anthologized in such notable collections as The Penguin Book of Homosexual Verse and Persistent Voices: Poetry by Writers Lost to AIDS.

Don’t miss our latest content! SpookyBooky is on social media: