Hidden treasure, ghastly ghosts and a doppelganger who kisses her man. There’s a lot going on in this 100-year-old gothic!

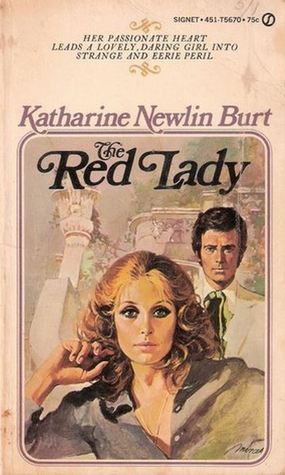

Katharine Newlin Burt was a pop novelist whose bibliography of westerns, mystery and romance spans from 1912 to 1975, when she was well into her 90s. The Red Lady originally appeared in 1920, but the writing style feels as mainstream as more modern gothics. No surprise it was dusted off in the ‘70s when publishers ran out of new spooky books to print.

Burt was ahead of her time with a satisfying romance element, eerie atmosphere and solid mystery. There’s even dialogue suggesting a movie might be made of the protagonist’s adventure. A forward-thinking reference seven years before the first talkie that shows she really had a pulse on pop culture and current trends. As it turns out, The Red Lady never became a film, but nine of her other books were adapted for the movies in the 1920s.

It’s a lean book that doesn’t waste time getting into the mystery. Surprisingly feministic as well. Gothics of the ‘60s and ‘70s often portray naïve women who comically fail to connect the dots of all the clues laid in front of them. Burt’s heroine, however, is pragmatic. She confronts the doppelganger and astral projection issues head on, conducting experiments to solve the mystery (and murder) with precision and impressive time management.

Though a calculating heroine is refreshing, I understand why it’s rare in literature to see one this efficient. Her smarts leave no time for the imaginative supernatural elements to run wild. The sizzle of mystery goes cold just as fast as it heats up.

In its climax, the momentum of the story really slows to a crawl during what must be the longest villain confessional on record. While our heroine is tied up, the villain uses at least fifty pages of uninterrupted dialogue to clarify exactly how and why it was all done. The speech doesn’t just resolve the mystery, it is a detailed report of every microscopic action taken. Mysteries you didn’t even know were mysteries are explained via this dissertation. Though it doesn’t say, I hope the villain kept a glass of water nearby during such a lengthy presentation.

Despite these weaker moments, however, there’s plenty of adventure and surprise to keep the story interesting from beginning to end. The writing style is breezy and fresh, which is rare for the 1920s. Burt clearly writes for entertainment over posterity, and the irony is that this has made her more enduring than many of her high-brow peers. I’m certainly captivated enough to want to pick up more of her books.

Don’t miss new reviews! Follow us on social: