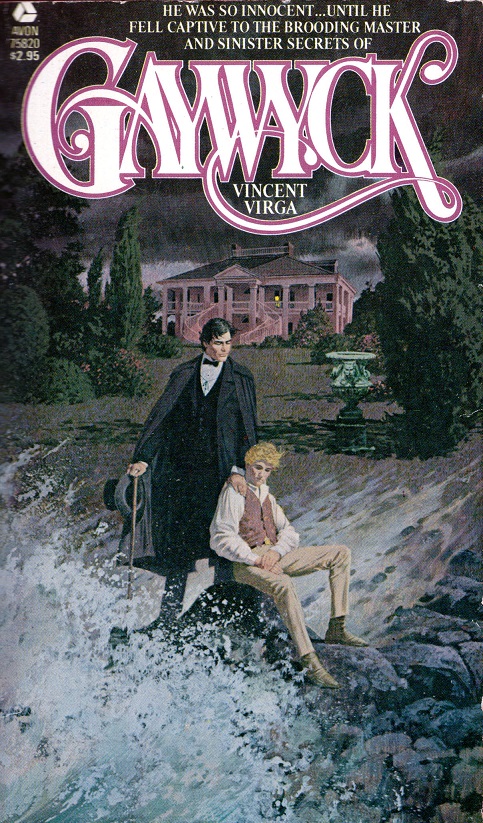

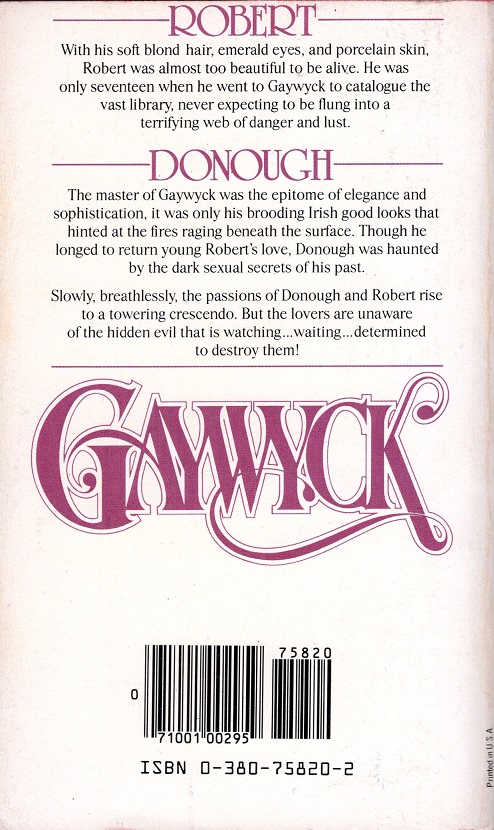

Gaywyck was a sensation when it appeared in 1980. Critics across the US and Canada heralded its excellent prose and landmark existence as the “first gay Gothic.” Though the peer-reviewed journal Gothic Studies recently debunked this claim, having unearthed an earlier (and better) Gothic novel with unambiguous queer characters from the Stonewall era, there are still these forty years where Gaywyck held onto the title.

More important than Gaywyck’s claim of being first, however, was its mainstream appeal. It was popular in the gay community, but also a favorite among women and straight men who enjoyed the genre. The first edition ran 45,000 copies and sold out quickly, as did the second printing of 55,000.

The timing was perfect—just barely pre-AIDS panic, and when an appetite for this kind of book was strong. By 1980, Gothic Romance paperbacks were largely forgotten, exhausted by an overabundance of supply and lack of quality. Gaywyck gave the genre one more jolt—a nostalgic return to a beloved literary space, but (finally) with new creativity.

Sometimes a novel will catch lightning in a bottle—become exactly what the public needs at that particular time. This was that kind of book. No matter how we evaluate it today, it was right for the moment, and an understandable salve to many gay men during the excruciating final years of their life.

There is still a lot to love about Gaywyck today, of course. The prose is generally quite exquisite. The hidden homage to Gothic tropes and classic cinema are fun easter eggs for the literary-minded. There is a solid sense of mystery and intrigue throughout. The romance is, in the end, sweet.

Where it struggles, I think, is an overabundance of characters who never quite jump off the page. With few exceptions, personalities are not unique enough to avoid blending. This ambiguity of character is necessary for one twist to make sense, but it rarely makes for enjoyable reading. The pages do not turn easily. And as someone obsessed with Gothic, queer, and historically significant literature, I should have devoured it all in one sitting. Instead, it took months.

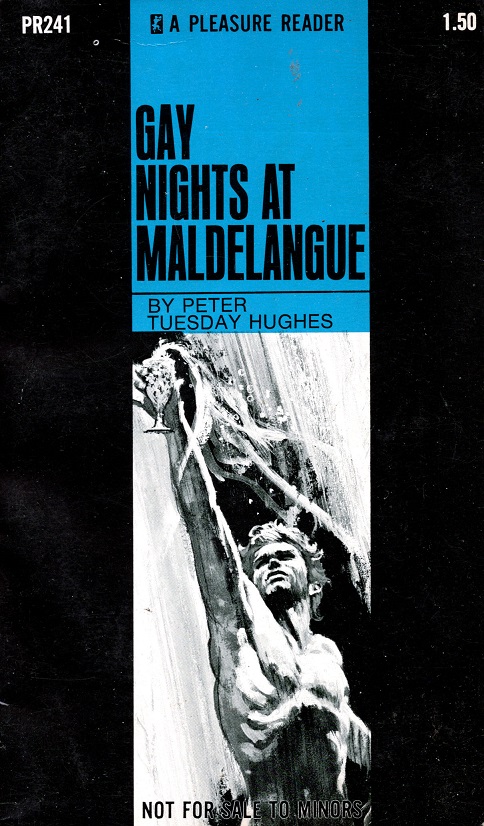

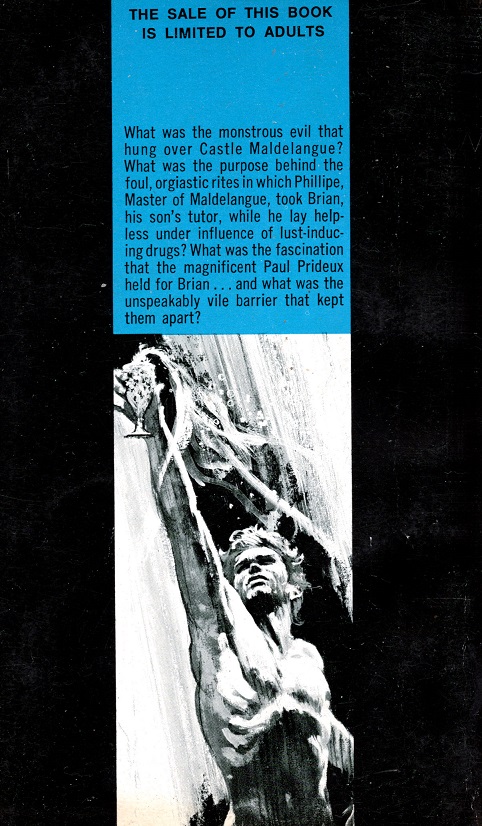

Meanwhile, Gay Nights at Maldelangue (1969), the real first “Gay Gothic” as identified by Gothic Studies, is written at a pulp pace, with every word thrusting the story forward and delivering dynamic personalities at every turn. Maldelangue has exceptional prose, as many—if not significantly more—Gothic literary references, and is surprisingly far less closeted despite being published a decade earlier. It’s unfortunate this novel is not as readily available as Gaywyck since I consider it a canonical example of the “Gay Gothic” and not one for scholars or enthusiasts to miss.

Keep the discussion going! Follow us on social media: