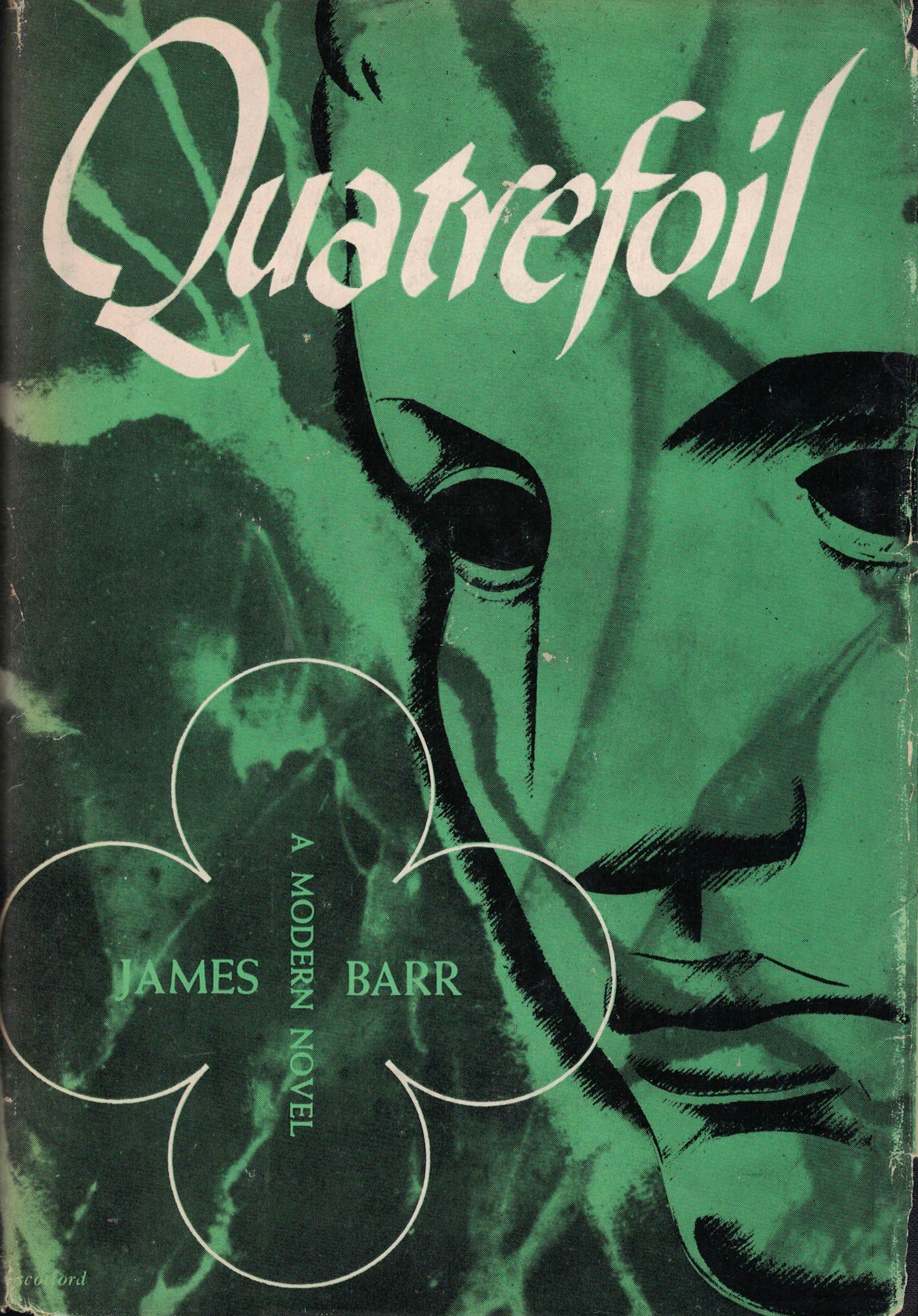

From an historical perspective, Quatrefoil is immensely significant. It is known for being the first American novel to depict gay relationships in a positive way. In the 1950s, Quatrefoil (pronounced cat-er-foil) became the bible for battling suicidal thoughts and embracing monogamous love, while simultaneously masquerading as straight to avoid blackmail and social ruin. Often the plot functions more as self-help than fiction. Tim and Phillip, one more experienced with his identity as a homosexual, the other still coming to grips, serve as stand-ins for readers going through their own journey.

Given this historical context, it’s no wonder the book became such a classic—and deemed so “obscene” that Greenberg, its publisher, was indicted on a federal charge of “sending obscene material through the mail.” After five years of legal woes, they eventually settled on a $3,500 fine and promised to keep the novel out of print. All this hullabaloo, mind you, for a book with absolutely zero sex scenes—not even a kiss! The only “problem” was its depiction of gay love in a positive light.

The novel is also significant for its post-WWII context. Literary scholar Drewey Wayne Gunn went so far as to consider it “one of the most important postwar documents.” Indeed, it is hard to imagine a better inside look at late 1940s gay issues in the military.

As obscenity laws finally relaxed in the 1960s, reprinted editions were available to a new generation of readers. These editions are likely what David Irwin and Dick Hewetson read, inspiring them so much that they eventually opened an entire lending library of queer literature to the public. They named it the “Quatrefoil Library” in honor of this influential book. The library, located in Minneapolis, continues to be a vibrant community and resource for every sort of queer texts.

All this juicy history aside, the novel doesn’t hold up so well from an entertainment perspective. Anthony Slide, a scholar who’s even nerdier than me about forgotten books with historical significance, admitted the novel is “overwritten, overwrought, and peopled with characters that seldom break through the fictional veneer.” That’s certainly a fair criticism.

The first half is almost insistent on making the main character disagreeable, but worse than that is how exhaustively veiled the sexuality is. Barr overwrites, because he intentionally wants to bury gay feelings beneath the weight of everything else. Totally accurate to how a frenzied 1950s gay mind would have been, and I understand how such hints would have enthralled its original audience, but we’re spoiled enough now that this style of writing makes many chapters exhausting at best and practically unreadable at worst.

The final quarter is considerably stronger, however, and the ending—hated by many—is actually quite profound, if not unnecessarily tragic and somewhat confirmative to hetero expectations. It took me four months to slog through the first three hundred pages, but I devoured the last fifty in two sittings.

I was surprised how much of the “advice” remains relevant. Barr’s 1950 perspective on navigating homophobic family and society while still pursuing your own gay happiness is, sadly, still a dilemma. Blackmail is less of an issue, and we can’t be discharged from the military or sent off to jail for violating sodomy laws, but homophobia is not dead. Society at large is more accepting, but families are still torn on this issue—and that’s the hate that hurts the most.

Keep the conversation going! SpookyBooky is on social media: