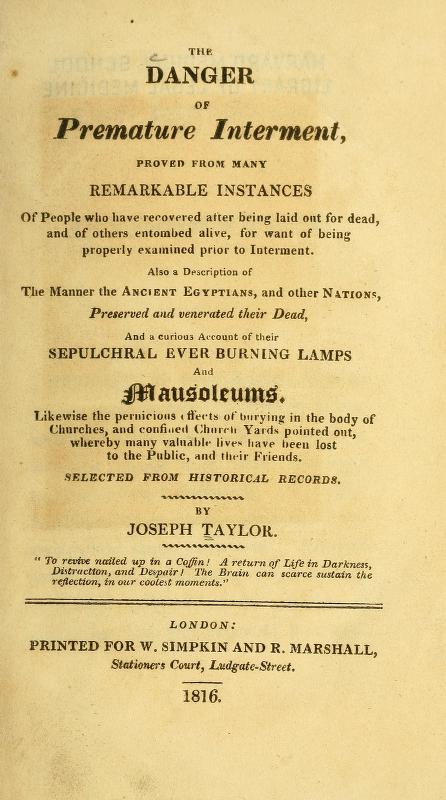

First published in 1816, when Edgar Allan Poe was an impressionable seven years old, this “science” volume chronicles reported incidents of premature burials, re-animated corpses, and bizarre embalming methods. It even finds time to get into politics, advocating for new laws that would make burial illegal within church yards and city limits.

Poe scholars point to this text as a possible reason for the author’s obsession with alive burials. Even if Poe never read it, its existence shows there was a general unease about premature interment at this point in history. Such evidence can further be found in early nineteenth century coffin technology which might include literal bells and whistles to alert a passing sexton.

Certainly there are enough unnerving “true” stories in this book to give one nightmares. The author is not as descriptive as Poe when it comes to the agony and torture of suffocation, but neither does he shy away from certain gory details. The anecdotes, pulled from lore, old newspapers, second-hand hearsay and other sources, are generally short and to the point.

There are stories of seeming corpses who revive at the first cut of an autopsy, and others who sadly revive after too many cuts. Stories of graverobbers anxious to cash in on jewels laid to rest, only to be startled by the victim, alive in their coffin. Wrongfully accused persons sentenced to the gallows, where, appearing dead, later revive and live a healthy life as if by miracle.

Because of their brevity and clarity, such stories remind me of Halloween campfire tales. The slightly baroque language only makes them feel more real, even if many come across as balderdash with our enlightened understanding of science. Still, it’s hard to get the images out of your mind.

A mistrust of doctors, something we still relate to in modern times, is another reason for alarm. Seeming corpses proclaimed dead and speedily buried on doctor’s orders are often the cause for error. Family members can be just as stupid. The author warns that your loved ones might be tempted to place your corpse in a cold location, such as a barn, which only makes the matter worse. One should warm the corpse first. This simple step is often sufficient for reanimation.

Particularly unnerving are the tales which validate my own family lore. According to my mother, my grandfather caught the 1918 flu and fell so ill that he appeared dead. Allegedly they scooped up his feeble body and dumped it into a pile of festering corpses. He became alert in time to escape the mound of dead bodies and avoid premature burial, but the close call scarred him for life.

In this book, Taylor writes of earlier plague years, where similar incoherent persons were mistaken for dead and promptly buried alive. Yikes!

Some of the “miracles” in this book can be explained with our modern knowledge. Such as “blowing breath into a patient’s mouth” to revive a dead person. As for all the dead bodies which revived after being swaddled in a blanket or warmed up next to a fire, I’m not sure what to make of that. Perhaps these persons were victim of a cold-induced coma?

I’m also interested in the poison vapors the author speaks of. A major argument for his belief that corpses should not be interred in cities or church yards is that their festering rot will emit poisonous vapors into the air, capable of killing those who are exposed. Furthermore, he provides anecdotes to prove it can happen. The image of being killed by the noxious stench of a corpse is not something I will soon forget.

Overall, an intriguing artifact that may have oversized significance to Poe fans. A scan of the original 1816 text can be downloaded from Google Books.

Keep the conversation going! SpookyBooky is on social media: