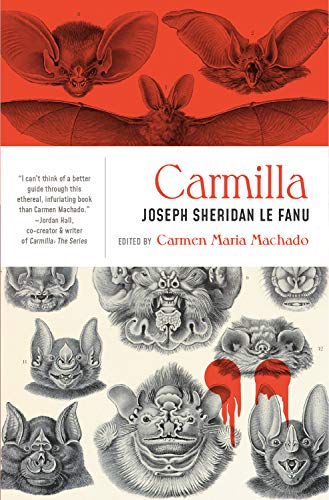

Lesbian vampire novel that pre-dates Dracula by 25 years? Sign me up! Carmilla (1872) was in fact a huge influence on Bram Stoker, as shown by many subtle references in Dracula (1897) and more obvious ones in “Dracula’s Guest”. Largely a forgotten classic, today Carmilla is receiving something of a revival thanks to an increased academic interest in queer artifacts and this new edition that’s edited by Carmen Maria Machado.

I’m a big fan of Machado, especially her brilliant 2019 memoir In the Dream House. She’s also an astute scholar of pop culture and distinguished LGBT voice, so the perfect person to offer gentle commentary via footnotes. This edition also includes some steamy illustrations not to be missed.

The story follows Laura, a secluded and lonely girl, as she’s befriended by a supernaturally beautiful woman who preys exclusively on other attractive young women. In addition to draining blood, Carmilla seduces with old-fashioned kisses and whispered affectations:

…with gloating eyes she drew me to her, and her hot lips traveled along my cheek in kisses; and she would whisper, almost in sobs, “You are mine, you shall be mine, you and I are one forever.” Then she had thrown herself back in her chair, with her small hands over her eyes, leaving me trembling (37-38).

The “You are mine” line here is an early example of a vampire’s possessiveness, which will be echoed by Dracula when he proclaims of Jonathan Harker: “This man belongs to me!”

Such sentences also depict precedent-setting vampire sensuality, where pain and pleasure are an enticing combination. While being seductively handled, Laura admits to “blushing,” feeling “embarrassed” and describing the encounter as “hateful and yet over-powering” — but it’s also clear that she’s enjoying herself. From the beginning, or at least as far back as John Polidori’s “The Vampyre” (1819), the literary vampire seems to be an outlet for repressed desire and exploration of taboos.

Consider this juicy paragraph, of which Machado observes: “If this isn’t an orgasm, nothing is.”

…sometimes there came a sensation as if a hand was drawn softly along my cheek and neck. Sometimes it was as if warm lips kissed me, and longer and longer and more lovingly as they reached my throat, but there the caress fixed itself. My heart beat faster, my breathing rose and fell rapidly and full drawn; a sobbing, that rose into a sense of strangulation, supervened, and turned into a dreadful convulsion, in which my senses left me and I became unconscious (69).

All these conflicting feelings described here are admittedly complicated, overwhelming, and a lot to wrap one’s head around. Is the scene supposed to be scary? Hot? Why not both? The reason vampires have been sexy for hundreds of years is largely because of this mixture of emotions, not in spite of it.

Like salted caramel, the vampire’s bite is a duality of flavors. Bittersweet. Being punctured about the neck is a painful sensation, but wrapping that feeling in a layer of ecstasy is how the vampire succeeds in an almost Darwinian way. By directing supernatural levels of pleasure toward the receptive partner, not to mention the enticing possibility of immortality, vampires make being their victim as much fun as possible. In a way that is scary—and hot—because the victim is willfully drawn to their own demise, enjoying every moment until it’s all too late.

Mosquitoes could learn a thing or two.

Follow our bookish social media…