A survey of 1960’s and ’70s gay pulp fiction reveals that sequels were scarce. Many of these books had impressive print runs (over 100,000) but rarely did any one title warrant a narrative continuation. The plots and characters weren’t exactly designed for posterity. Instead, their pleasures were often of a disposable nature, to the level of being tossed out with garbage upon reaching aphrodisiacal fulfillment. The idea that people might read, collect and obsess over pulp fifty years later probably sounded laughable at the time.

Nevertheless, there were fan favorites and landmark publications among this ocean of cheap, sleazy paperbacks. Some titles generated multi-book series, spin-offs, parodies and, of course, sequels. Notable examples of the era include the 2069 trilogy (1969-1970) by Larry Townsend, The Man from C.A.M.P. series (1966-1968) by Don Holliday, and Richard Amory’s bestselling Song of the Loon trilogy (1966-1968). Amory’s books sold in the millions and even had a movie adaptation.

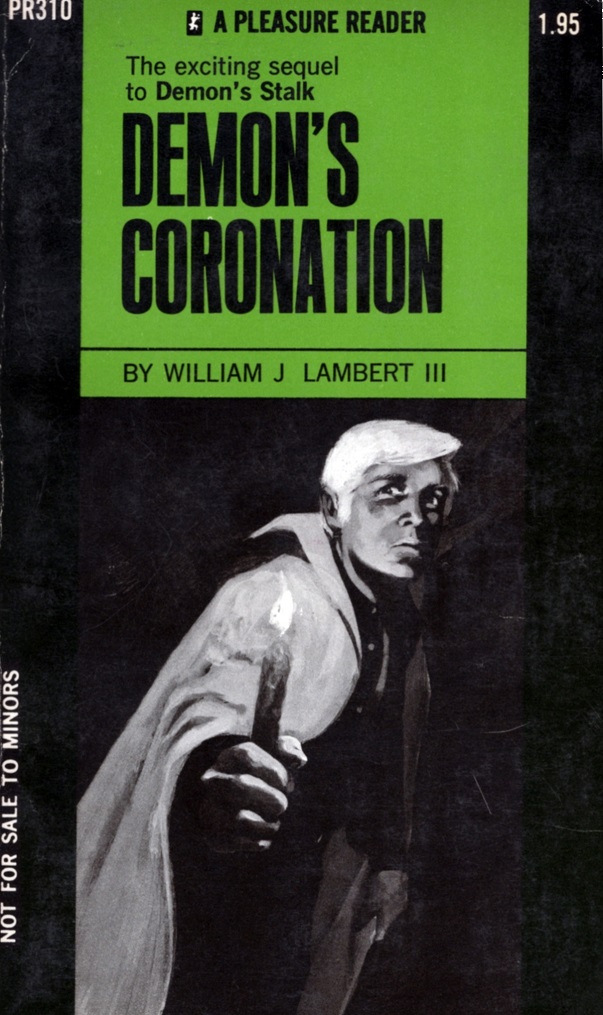

Demon’s Coronation (1971) by William J. Lambert, III, is another example, being the dramatic second half of Demon’s Stalk (1970). If you’ve read my review of the first book, you know I’m a fan and would consider it not only a fabulous example of queer pulp, but also the horror genre at large.

Audiences of the day must’ve shared my enthusiasm. At least enough to recognize the title and desire a sequel. Certainly both books are memorable, with unexpectedly vivid characters, fiery love scenes, and genuine terror. Written specifically for a queer audience, there’s a unique perspective that’s not found among the renaissance of other ’70s satanic-themed fiction. Lambert’s demon books were among the first, hitting shelves shortly after Rosemary’s Baby (1967), just before The Exorcist (1971) and some years ahead of Jay Anson’s The Amityville Horror (1977). It also happened to be the year of Charles Manson’s public trials (1970), assuring that readers were seeing Satan everywhere, even in their pulp.

Demon’s Coronation begins eighteen years after the frightening events of the previous novel. The satanic civil war is ongoing, with Anaroth still seeking to dethrone Lucifer and rule “New Hell.” Lovers Etienne and Serge have sold their souls for eternal youth and hellish political positioning. Anthony, a psychic and a previous lover of Etienne, is the last hope for redemption. But he is subject to constant temptation by those anxious to keep him from meddling in underworld affairs.

As with the first novel, Lambert’s thematic energy focuses on contrasts: Heaven vs. Hell, reality vs. fantasy, wealth vs. poverty, and opposite ends of social hierarchy. After a nearly two decade time jump, however, it’s fitting that the most predominant yin and yang is of youth vs. maturity.

Anthony, who already felt the pangs of middle-age in Demon’s Stalk is now well into his sixties. Still the target of demons, he casts spells over his bed nightly to prevent the same fate of others on the side of Heaven. He nearly backslides into destruction, however, when Etienne visits via astral projection. Etienne offers the satisfaction of enjoying his eternally youthful body, if Anthony will break the spell. Each time the old man recalls his senses only at the last moment, narrowly avoiding certain death.

Though Lambert would’ve been a young author at the time, Anthony’s wizened struggles are explicitly conveyed with even greater poignancy than the dilemmas of the youthful characters. There’s no shying away from the lamentations of a manhood that’s “wrinkled and lifeless,” for example, even when these details would traditionally be avoided in erotic writing.

Miraculously, however, the scene does heat up when one of Anaroth’s temptations aims to prove that Anthony’s “sap has not drained.” A demon hunk asks, “Is the well dry? Or has there merely not been anyone skilled enough in fixing the pump?” The old man is unable to resist the coaxing of this sexy experiment, and thus seals his fate, but he does get to rejoice in a temporary miracle: “To be hard again! To be reborn! How impossible! How wonderfully unbelievable.”

While some may find this scene off-putting, or perhaps what could be a bizarre commercial for Viagra (not yet invented, of course), my favorite thing about Lambert’s novels is his willingness to show more than just beautiful sex. There’s ugly sex, regretful sex, horrific sex and scenes like this, which are oddly pleasant even if a mature character is the star. It shows, I think, the vast possibilities that can happen in the bedroom, and not all of it is pretty.

It’s fair to say that the overall thrills of the sequel are not as spectacular as the masterful world-building, erotic delight and horror of the prior novel, but it’s also unfair to judge each book individually. The first tells a story of ambitious youth and ceaseless passion, while the other takes on the terrors of advanced age and desperation. Both are necessary to reveal a dark side of the human experience, or at least fifty-odd shades of Hell.

As a whole, the imagery is Faustian, Freudian, Marlovian, and still capable of scandalizing these fifty years later. Furthermore, time has not reduced its liberating qualities, for queer readers and straight alike. Pulps are, by nature, designed to push boundaries, explore secret turmoil and imagine bizarre desires. No other genre would dare venture into these taboo topics with such biting confidence. Sometimes there’s a good reason for that, but often—as is the case here—the result is an enlightening, virginal reading experience unlike any other.

It pains me to know how many of these books were thrown away and that there doesn’t appear to be any interest in re-printing pulp fiction. Finding a copy of either Demon title could be a years-long endeavor, and finding both to read the full story is particularly challenging.

Scholars are starting to pay more attention, however. Particularly with regard to the pulp’s impact on the LGBT movement and sexual liberation. The Golden Age of Gay Fiction by Drewey Wayne Gunn is probably the best literary analysis of this era and a must-read for anyone interested. There’s hope, I think, that we’ll eventually see these historical texts restored and available once again.

!!!BONUS INTERVIEW!!!

I had the pleasure of interviewing William J. Lambert, III, aka William Maltese, about this book, his inspirations, and other factoids from the era. Here’s a copy of our interview:

JUSTIN: Demon’s Coronation is one of the few sequels found in your long list of publications, and of pulp fiction in general. How did writing the second book come about?

WILLIAM: The truth is that I find series truly difficult to write, in trying to remember all the characters, all of their descriptions, all of their peculiarities, all of their actions and reactions with the other characters. With the expectation of 40,000 to 60,000 words, per book, it was often difficult to squeeze in all I wanted to say. I suspect the cause of this sequel to Demon’s Stalk was an end of the first book with enough immediate interest to me, and to my publisher, Greenleaf Classics, for me to carry on.

JUSTIN: Freud is referenced in this novel, and his theories are certainly relevant in many of your works, Oedipal and otherwise. How impactful were Kinsey, Freud, or sexual psychology in general to your creation of these vivid characters?

WILLIAM: Sexual psychology has played a great deal in my writing, in that it’s always a good thing for an author who writes about sex to know the sexual who, what, why, where, when, and how of his characters. It provides insights into who they are and why they do what they do, instead of seeming to act on pure impulse. And it helps if the author has viable authorities, like Freud and Kinsey, to back him up. I remember a whole genre of early pulp books (by Barclay House/Brandon Books?) that masqueraded as psychological studies, by supposed authorities, who used the likes of Oedipal Complex and Electra Complex, as a parenthesis for writing sex about incest; thereby, providing that necessary social redeeming aspect needed to separate it from pure porn. During all of my venturing into that format, I had the opportunity to imply causality by referencing Freud, Kinsey, and all the rest of the recognized sexual psychologists. And, I’m sure my military observations have been helpful, if just because most authors draw from their personal experiences if just because it would be ridiculous to avoid using such rich information sources.

JUSTIN: Knowing you were still quite young when writing this novel, I was surprised by how beautifully you explore Anthony’s struggles with old age. As a lad, were you an “old soul” and thus capable of easily imagining these conflicts, or were there any other sources of inspiration?

WILLIAM: Was I/Am I an old soul? Well, I have been told, more than once, that I’ve lived other lives. I even know one dear friend who assures me we survived the German Blitz of London together. I remember once, in a gay restaurant, the waiter asked me how old I was, and I gave him an age twenty years beyond the actuality. My dining companion was shocked in never having heard anyone he’d ever known, besides me, provide an age older, rather than younger, when asked. Go figure! I’ve always just been aware that we all grow old and should be smart enough to recognize the struggles that come with age if just so we’re able to cope with that inevitability when it catches up with us.

JUSTIN: In Draqualian Silk you reference the moment when you chose to write fiction. It was after reading a pulp novel and deciding you could write something just as good. Do you remember what book that was, and which ‘golden age’ pulp writers did you find inspiring?

WILLIAM: I vaguely recall that it was a book by Peter Tuesday Hughes but don’t hold me to that. It might have been one from Richard Amory’s Loon Trilogy. Both Peter and Richard were Greenleaf authors at the time. As for finding any of my “golden age” authors inspiring, I’m afraid I made it a point, after reading that first book, and getting my novels published, to steer clear of my peers and their writings. I was always afraid that I might end up inadvertently copying another author’s plot-lines.

JUSTIN: I’m a huge fan of ’70s gothic romance and was surprised to learn that many of your contemporaries wrote these books as well, such as John Kimbro (who wrote gay pulp as Kym Allyson and bestselling gothic romance as Katheryn Kimbrough) and Victor J. Banis (aka “Don Holliday” and numerous pseudonyms for gothic romance). Did you read or write any of these ‘Women Running from Houses’ books?

WILLIAM: You know, I was always a big fan of Daphne du Maurier and Anya Seton, but I didn’t get around to writing any heterosexual romances—and those were more adventures than gothic—until I wrote my three Anna Lambert Carousel Romances in the late 1970’s. Those were followed by my three Harlequin SuperRomances and three Heritage House Romances as Willa Lambert in the 1980s. I did another romance novel, under my own name, for Passion in Print, and a couple more Willa Lambert romances for Wildside/Borgo Press, in the 2000s. All of those well beyond the golden age of pulp fiction when John Kimbro and Victor J. Banis checked in.

JUSTIN: In your essay “On Being There … But Not” I learned that your real name is actually William J. Lambert, III. Amid all the pseudonyms, I wasn’t sure if you’d ever revealed yourself. Impressive to be a third! I don’t know many families that go past Jr.

WILLIAM: When I started out writing those early pulps, my books were all published under my original name, because I’ve never been ashamed of laying claim to what’s mine. As for the “III”, my family does go back to being in North America even before the American Revolution. The “III” has so long been a part of my name that it was just natural, still is, for me to include it … whenever. I can’t ever remember thinking, even at the outset, that my real name on my gay books would forever have me pigeonholed as a gay writer, which it never did, maybe because, by then, I’d published my he-man South American treasure-hunting adventure for Argosy magazine. Truth is, I’d probably still be publishing everything under my own name, to this day, except that, back in those pulp days, I was so prolific that pseudonyms were used at the request of publishers who didn’t want readers to think that I was putting out books on an assembly-line basis, even though I was putting out books on an assembly-line basis. Eventually, of course, I ended up with so many nom-de-plumes that it became just way too complicated to answer to Chad, Cort, Scott, Doug, Christopher, et al. A time was reached when I just decided to consolidate them all under the one name, if just to have them all in one place like Amazon. I figured William Maltese’s over two-hundred books were likely to impress far more than Adam Maye’s one book, Karl Klyne’s two books, Mitch Stone’s one…

JUSTIN: I counted an astounding 36 different pseudonyms in all. Any funny stories about how you came up with a certain pen name?

WILLIAM: In a word – No. I did want to use the first name Wilhelmina for my Harlequin SuperRomances, but the publisher insisted that it was just too long for any book spine; so we compromised with Willa. Other than that, it has always been my trying to find a name that I just liked. That’s always been the case, too, in trying to pick character names.

JUSTIN: What’s the pulpiest novel you’ve written recently that is available in bookstores?

WILLIAM: My most recent novel, William Maltese’s Flicker: #2 Book of Ascendancy, is intended for a mainstream audience, albeit with a couple of gay characters (by the way, it’s a sequel that took me ten years to write), but I haven’t left the pulp gay genre behind. My mini-novel Mason came out early last year and would interest pulp fans, I think. There’s also my full-length books I, Vampyre and ReVamping Delaney which fit that bill.

JUSTIN: Adding them to my reading list now! Thank you again for your time and sharing insight into this fascinating world of publishing. Hope to chat again soon.

WILLIAM: My pleasure, any time.

More reviews of the obscure and unusual to come! Follow us on…