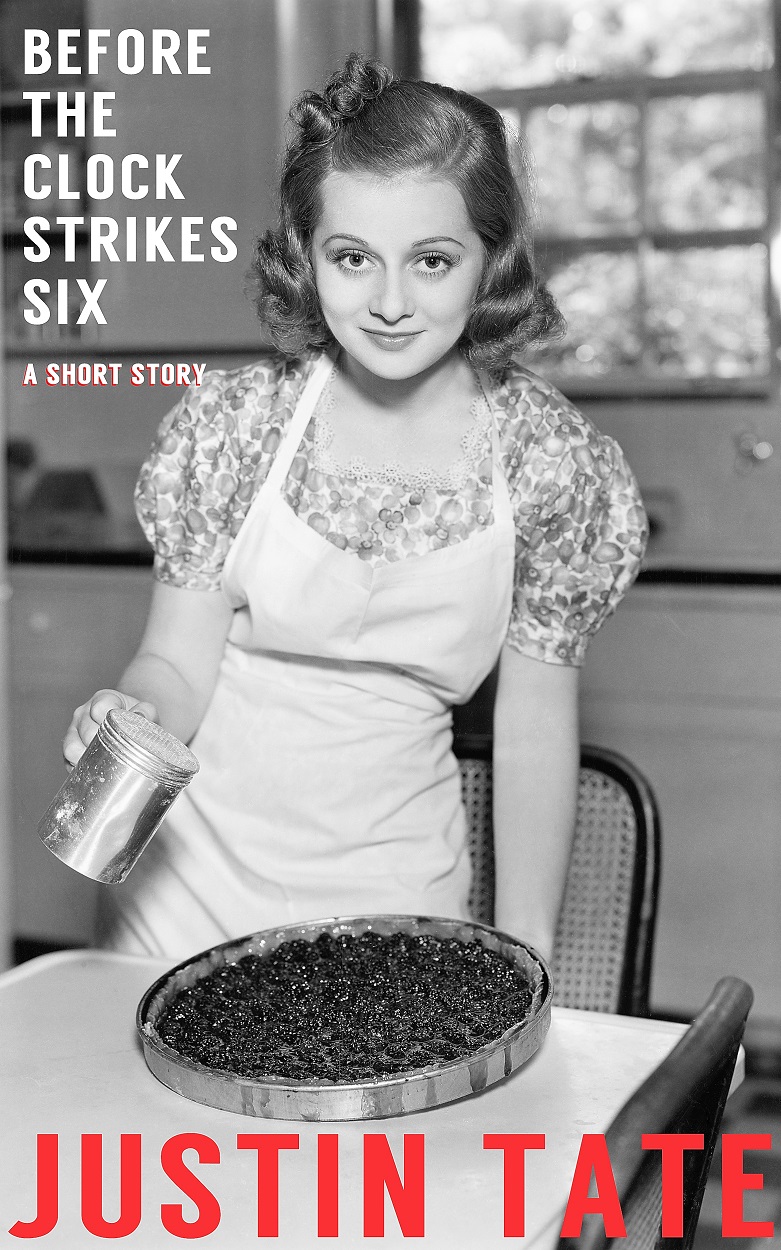

A woman preps in a kitchen. Like a robot, her movements are both jittery and fluid from repetition. She reaches into cabinets with urgency, gathering oils, jars, utensils and cookware. Ladles and tongs rattle in her grasp. A package of flour slips, bursts and clouds the air. The refrigerator is emptied onto the counter, one item at a time, all in a row. She plucks a few spices from the rack, reconsiders, and brings down the complete set. Her eyes dart toward the huge grandfather clock in the living room. It is five minutes before five.

She surveys the ingredients scattered about the counter. There is no logic to the array, it is simply all that she can find. Tonight she is preparing a new recipe from an old book. Anything can happen.

The recipe calls for one-quarter teaspoon thyme, two teaspoons vinegar, a tablespoon of Ocean Essentials brand sea salt (with iodide, a necessary nutrient) and one bay leaf to simmer in boiling water. She is surprised to see a pot of water already on the stove, churning with excessive heat. She must have prepared it earlier and forgot. It is a strange thing to forget, but not inconceivable. After years of redundancy some tasks can be completed without thought.

She removes a bay leaf from the spice rack and dangles it over the aluminum stockpot. She is reluctant to let it fall. The boiling water is tempestuous, heat bubbles popping and foam hissing around the edges. There is a morbid, murderous sensation as her fingers twist above the hellish current to release the herb. The bay leaf floats down like a feather, bobs with the pulsing waves. The recipe is unfamiliar and, by choosing it, she feels somewhat responsible—guilty—as the leaf’s green sustenance bleeds out.

The grandfather clock chimes. She turns away from the scene—the bay leaf, the oceanic waters, the measuring spoons—and pauses to hear the hours toll. She visualizes the cogs, weights, spindles and springs ascending and descending behind the clock face. She sympathizes with their life of infinite rotation. There is no levity in the chimes— . . . two . . . three . . . four—only duty.

. . . Five . . .

The final reverberation shakes the kitchen with clamoring dissonance. The clock is evil, she thinks. A dark mechanism designed to overwhelm a room with its towering presence, its ticking and gonging, reminding all that their pathetic lives cannot escape the circular loop of a day. She fantasizes briefly about throwing the clock out—chopping it into firewood with a sharp ax—before returning to the stove.

The boiling water is on the brink of bubbling over. She stirs it with a wooden spoon and watches the bubbles momentarily abate before springing to life again. There is something to be said about that, she thinks. About the mysterious persistence of boiling water.

She wonders: is she more like the boiling water or the old wooden spoon? Water—in its natural state—is docile and non-threatening. It may be used to bring life to others but has few purposes for itself. If not drunk, water may sit at the bottom of a well or drip in a cave. It may decorate a spider’s web or slosh down gutter drains. At best it may flood and torment society. But eventually—when its time has come—the sun will rise and turn all to vapor. What is left, if anything, will be a worthless speck of salt—without iodide, a necessary nutrient.

Of course boiling water is different. Boiling water can kill if it wants. It can melt human flesh or destroy the same weeds that suck up its soul. It is powerful by nature and all must bend or dissolve to its authority.

She likes the allure of boiling water; the delicate entity that can transform itself into a ruler. Still, she cannot quite compare herself to it. It is too dominant. Too independent. She is more like well water or the old wooden spoon: a utensil. Something used to serve somebody else.

She reduces the heat and picks up the book. She gazes at the recipe for some time before realizing that the pages must have turned. Fluttered, perhaps, by a breeze from the open window. The recipe on the page is for blackberry pie which requires entirely different ingredients and, moreover, there is already a blackberry pie cooling on the windowsill, its form hidden behind stained curtains. She can smell its lurid scent haunting the kitchen.

The pie’s presence is a mystery. Did she bake it? Absent-mindedly preparing a pot of water may be possible, but an entire pie? Surely not.

She imagines herself standing zombie-like over the counter, blank-eyed and vacant, sifting flour, cutting butter, congealing berries, pre-heating, donning oven mitts and placing the pie on the windowsill to cool. It is too much. She refuses to believe it. She is forgetful and damaged, but her mind is still sharp.

And yet there is another concern: why blackberry? The last time she prepared a blackberry pie she had been punished. Why waste time on a forbidden dish? What would be her motive?

Wherever the pie came from, it must be tossed out.

She would dispose of it now except that she does not dare draw back the curtains to see if the pie actually exists.

Returning to the book, she tries again to find her place. It is a nice book, old and yellowed, with pencil renderings of each recipe. She cannot remember the title of the dish she is preparing and browses them all in hopes one will sound familiar. She turns and turns, but each recipe seems indefinitely right or distinctly wrong. The pie appears to be printed on every other page, as if sending a message.

As she reads, the grandfather clock fills the air with stagnant, impending doom. Bad things will happen when the clock strikes six. They always do. It is as expected as commercial breaks during a telecast. It is like—well, it is like clockwork.

Soon after the sixth chime she will hear a car door slam followed by the sound of her husband’s oxfords on the pavement. His steps will be slow and calculated. He knows that she is under a deadline and thinks himself kind to give audible cues. He will jangle keys before inserting one into the lock. He will turn the lock so that it clangs. He will open the closet with a bang and grunt as he tucks away his briefcase. This will be his final warning.

The surprise will be how long it takes him to emerge from the hallway into the dining room. It could be thirty seconds or fifteen minutes. He varies this on purpose, she thinks, in attempt to catch her unprepared. If dinner is not served precisely to his tastes, he will beat her.

She learned this shortly after their honeymoon. A soup too cold, a soufflé too crisp, too many ice cubes or not enough—any minor mistake would be enough for him to strike. Over time she developed a vague understanding of his requirements, but there was always the chance that something unexpected would set him off.

The incident with the blackberry pie occurred on their sixth anniversary. She was determined to prepare a dessert that would prove herself worthy of him. He hit her, she believed, out of love and a desire to help her achieve. He wanted her to be perfect. She wanted that too. Housewife instincts told her that perfection could only be expressed through pie, so she spent the day picking fresh blackberries and isolated herself in the kitchen to concoct a masterpiece.

The problem was that her husband had, long ago during their short courtship, mentioned an allergy to blackberries. She had no recollection of this conversation and wondered if, in fact, he ever spoke of it. When he saw the pie he immediately interpreted the mistake as a violent act of disobedience. He accused her of trying to mock him, of wanting to collect insurance money, of desiring to leave him and engage in an illicit love affair.

Stunned, she had no time to react before being shoved to the tile, forehead smashing against the counter. He pinned her against the floor with one knee and twisted an arm behind her back. He roared accusations until her ears rang.

She tried to explain the misunderstanding, but her words came out as blubbering nonsense. Every time she sputtered he yanked her arm back further until it snapped. The sound was like tree branches in an ice storm. At first she was only shocked by his cruelty and then all she could think about was the pain. It roared through her arm, up her spine and into her brain. His knee grinded deeper into her back, pushing her face against the tile. The last thing she remembered before blacking out was having a fear that her neck would crack.

At some point he must have moved her. She woke sprawled out on the sofa, a pillow tucked awkwardly beneath her bruised scalp. The pain was full-bodied and heavy. She was too drowsy to move, so she slept. The clock woke her the following afternoon when it struck four. Her neck and back still hurt and her arm was limp, but she could move.

She sat upright on the sofa for several minutes, expressionless, watching the second hand on the clock loop round and round. It was only two hours before six. He would be home soon and he would be hungry.

If she ran away he would not be able to stop her. She could find refuge. She could survive. But if she stayed, there was the chance to make amends, to avoid being a failure. Part of this, she thought, was her own fault. He said he told her about the allergy long ago—why had she been so stupid to forget? Of course he would react that way. It did look suspicious. She could be better from now on, start getting things right. Their marriage did not have to end in tragedy.

She decided to stay, but vowed to never bake another pie.

Until now?

Chilled by the memory, she searches for a distraction—something to keep her mind off the thing on the windowsill—and sees the boiling water. At least there is that. And the bay leaf, the precious bay leaf, drifting so hopelessly among the tides. She wants to hold it, to caress it, to whisper soothingly that everything will be okay. There is thyme, too, pepper and paprika; the jar of salt sitting pretentiously away from the others, as if to say, I contain iodide and you don’t.

It is important that she do something. She cannot simply stand there resenting the salt and daydreaming about the pie. If the recipe is lost forever, she must invent her own.

On the counter are four lemons: thick-skinned, ripe and wet as if recently washed. No lemons were washed today but her frazzled mind ignores this detail. She takes up a paring knife and confronts the citrus. She slices into the lemons with satisfying strokes. It feels good to be back on task, to be preparing things for a purpose. The fact that the lemons serve no purpose is not important. There will be something in the book that calls for lemons. If not, she can squeeze the juice onto lettuce and make a salad. Her husband hates salad, but not as much as he hates an empty table. They will serve a purpose. She will force them to.

Halfway through the third lemon, the blade slips. It slams hard, severing the thin web of flesh between her third and fourth finger. It is a hateful, bloodless cut that shrieks with pain as lemon juice pours into the gash. She jerks, startled by the sudden, acidic bite.

She washes her hands. The soap stings—somehow worse than the initial cut. She grits her teeth and cries. She is hurt, of course, by the pain of the cut but more so by this additional failure. The lemons were a final attempt to improve an impossible situation and she has again shown herself incompetent.

She dries her hands on a paper towel and wraps it around the slit. She thinks about how many times she has been physically injured in this kitchen and wonders if the number is more or less than one thousand.

Behind her the boiling water bubbles over, plopping onto the hot stove with the hiss of snakes. She lowers the heat again and stirs. After a few circles the boil subdues.

With no other option she allows herself to be intrigued by the phantom pie. She turns to the curtains, watches them breathe with the breeze. A shadowy, circular object is visible atop the sill. Perhaps the pie is not an illusion after all. Perhaps she did make it herself, hours ago, while deep in thought. She might even risk serving it, just to see her husband’s stunned expression before killing her. At least it would be one act of defiance.

She approaches the curtains cautiously. A sense of destiny propels her forward even as her body weakens with fear. The tell-tale silhouette reveals itself again—it could be a pie or a landmine. She lingers a limp finger toward the red curtains, draws back at the touch of rough fabric. The shadow protrudes and shapeshifts. Something appears to spike out of the center. Fragrance rushes forward: baked crust and blackberry filling. It is the definition of pleasant and yet she recognizes the odor as foreboding and reminiscent of death.

Abruptly, she rips apart the curtains and confronts the object.

She recognizes the pie instantly. It is, on all accounts, an exact replica of the one she prepared years before. The same pie that enraged her husband. It has the same flaws—crust too thin, slightly burnt—and the same perfections—thick, gooey consistency a midnight shade of purple. There is even the same dusting of powdered sugar on top, a last-minute idea which had been entirely her own and not mentioned in the book.

The single difference is that this pie has a thirteen inch kitchen knife stabbed directly into its center. She can see herself in the reflection of the blade.

She grasps the knife by the thick, black handle and tugs, slowly at first, like Arthur testing the sword in the stone. There is no surprise when it emerges with ease. A splatter of bluish goo slides off the tip as she wields it in the air.

The knife feels good in her hands, familiar. A sense of electricity sizzles around the room, around her. If she did prepare the pie in a blackened state of unawareness, perhaps she knew that she would encounter it now, in these desperate times, with this willingness to be empowered. Whatever message the pie is designed to send, she receives it in the most murderous way.

Tonight, she thinks, her husband will eat what she serves.

She picks up the pie and carries it to the dining table. Curls of steam rise from the hot filling as it cools. The smell is overwhelming, dizzying. She sets a single plate on a decorative doily at the head of the table. This is where her husband will sit—this is where he will die.

She stabs the knife into the pie again. Let it stay there for now. She has much to do before the clock strikes six.

First she must clean up the kitchen. If he sees the mess he will attack before she is prepared. There is no time to put everything back where it belongs so she wheels an oversized trash can to the edge of the counter and sweeps everything into it with one arm. Glass, plastic, cartons and other containers clang at the bottom. When all is done the can is nearly full. The empty kitchen brings a mixture of relief and depression, like casting off conspirators and finding herself completely alone.

All that remains is the recipe book, salt, lemons and pot of boiling water. With time running short, she has to plot the murder quickly. He will fight back, so she must finish him off fast—but it is also important that he suffer. No need to be tidy. The image of her cozy kitchen splattered with blood is a pleasant one.

The grandfather clock reads fifteen minutes to six.

She returns to the pie, pulls out the knife and rinses it off. She locates a sharpener and strokes the blade against ridged steel. The grinding, metallic noise is like music. There should be some symbolism to the massacre, she thinks. After all, this is not a freak killing. It is retrospective self-defense. He needs a taste of her daily routine. Some inkling of the misery she encounters in this kitchen.

A recipe occurs to her. “Salty Demise” she titles it and is surprised to find herself laughing at the idea. It is not the type of recipe that can be found in her book, but it should be. She decides to write it out on one of the blank pages:

Salty Demise

(Prep Time: Approx. 15-20 minutes)

1. Submerge knife in boiling water, remove and pat dry

2. Soak blade in a marinade of lemon juice and soap

3. Sprinkle iodized salt onto blade

4. Serve hot

After scripting the recipe, she follows her directions to the letter. The salt sticks beautifully to the blade in the mix of lemon juice and soap. It sparkles in the artificial light, appearing decorative and whimsical, almost non-threatening. She likes that. A perfect deception.

It is six and the clock is striking. With the sound of each hour her confidence drains away. The knife almost drops from her hand as she props herself against the counter. The room feels as if it is swaying. Pain swirls through her arm, back and neck. It is only the memory of agony from long ago, she knows, but it feels crippling. What is she doing? What has gotten into her head? She is weak compared to him. He will laugh at her and beat her anyway. The knife will be slapped out of her hands like a toy and she will be helpless to retrieve it. Why did she have to make things worse?

As the sixth chime erupts throughout the house, she imagines that the walls are trembling, the pot rattling on the stove, dishes shattering. Cracks creeping from ceiling to floor, etching toward the kitchen where she stands. A cavern opens up, revealing the smoldering pit of hell. She can see herself falling into that pit, grasping uselessly for stray tree roots as she descends into darkness and heat.

Out of breath, steadying herself, she waits for the vision to pass. Her defiance, which seemed almost jovial earlier, has revealed its problems. She has been carefully trained to fear this hour, how can she expect herself to misbehave? She is supposed to be scurrying about the kitchen, adding final garnishes and testing temperatures with tiny thermometers. She is not supposed to be plotting to kill her husband. It is like going against the course of nature. Would a clock experience this conflict if it chose to run backwards? Can she, thus designed, do anything but comply with normality?

The answers to these questions will soon reveal themselves, she thinks. It is 6:01 and there is the distinct noise of his car pulling into the gravel driveway. She hides the knife behind her back and retreats to the far corner of the kitchen to wait.

She does not have to wait long.

The front door creaks open on rusty hinges—he is inside. She can hear his distant, hoarse breath in the entryway. The closet opens, shuts. Heavy footsteps on the carpet—he is approaching the hallway already! Any moment he will be in the kitchen, he will see her and be suspicious. He will attack.

She stiffens her grip on the knife and flushes with new energy. She has not given up yet. Perhaps a conflict is exactly what she needs. A death match. A big bang—something so horrific it spins her life onto a new course. There can be a struggle, if that is what he wants. How it happens is not important, so long as it ends with her standing over his butchered body.

One stab is all it takes.

One stab is all it takes.

She repeats this like a mantra, exciting herself, allowing herself to boil. She is no longer the wooden spoon, she thinks. She hopes.

Suddenly, there he is. Framed in the hallway. Tall, thick, dressed in a collared shirt. His sleeves are rolled up to show thin threads of arm muscle which have somehow remained from his adolescence. A receding head of dyed black hair is locked into place with some kind of lubricant. His face is the product of failed morning regimens: anti-wrinkle ointments, chemicals and pastes. The youthful charade is a poor performance, but she cannot deny that he remains attractive.

He is casual, unfurrowed and a little smug as he enters the kitchen with a newspaper under his arm. He probably made a good business deal today—if he is in the line of making business deals. She doesn’t really know what he does. If he ever told her, it was probably a lie.

He does look like a business man, though. Or a politician, maybe. Someone who can break laws and get away with it by wearing a suit.

She can see now how he must have conned her. A small-town girl, painfully single and desperate for stability, pursued by an attractive older man. Three dates and they were engaged. Why stop and think? Everything was going so well. He met all her criteria—handsome and well-off. Her friends approved, her parents approved. They were, in fact, once a celebrated couple.

When did their celebrity end? After the first sign of abuse? After he broke her arm? It is difficult to remember life outside the kitchen. She recalls a decision to stop speaking with friends and family once the bruises became too severe to cover with makeup—they would only tell her to suffer through it and, worse, know her life was as miserable as before—but had she ceased communicating with them entirely? Unlikely. And yet she cannot think of an example to disprove this theory.

He enters the kitchen at a brisk pace and stops halfway to the dining room. His murky eyes whip round in her direction. He is suspicious, but not necessarily of her—he is staring at something beyond her. He sniffs the air curiously, animal-like. Trying to identify his dinner, she thinks. Will he smell the pie? How can he not?

She braces herself further against the wall, putting distance between them. At any moment, she thinks, he will rush forward with hands reaching out for her throat.

He does not move or alter his gaze, however. Something is off. He is anxious and perplexed, even a little scared. How long will it take for him to react? Should she say something? Try to soothe his nerves before he becomes enraged? Probably so, but what would she say? The thought of uttering another “Hello, darling” is unbearable.

Eventually he walks on, seats himself at the head of the table and unfolds the newspaper.

He’s going to see the pie, she shrieks to herself. Hurry—kill him now! Kill him before he sees!

But, of course, she wants him to see the pie. That is part of the plan. He needs to know why this is happening and she needs to see recognition in those eyes before stabbing the blade between them.

He is reading something—a gossip article most likely—while she stands in the corner, holding her breath, preparing to end his life. How can he not sense the hatred in the room? The sweltering stench of blackberries and murder? It is all around her, swirling, pulsating; a hanging fog that creeps just below the throat. What does he think is going on? That she is standing there, frantic and frozen, to allow him time to settle in? Is he waiting for her to serve iced tea and pot roast?

She is about to act when he turns in his seat. A corner of newspaper folds down, allowing him to squint in her direction. He looks puzzled again, as if noticing a tiny speck on the carpet and debating whether it is a stain or lint fuzz.

She cannot stand it any longer. Whether he sees the pie or not, he must die. If she is going to do it, she has to do it now.

The knife comes out, salty, lemon-soaked and still hot. She raises it in the air and lunges at him. She shuts her eyes tight to avoid seeing the bloody act. She is afraid witnessing it will cause her to stop. When all is done she can observe every drop of gore, but not until then.

Her attack is on target. The knife swings down and penetrates flesh. She can feel the blade ooze through tendons and hit bone. She rips it out and brings it down again, harder, faster. More soft flesh. Again—she hits something hard. His skull? No time to ponder, she arches back and takes another slice, throwing all of her emotion into it, all of her anger. He must be dead by now, but she cannot stop. There is still too much he has to pay for. She swings again—the handle is slick with blood, grainy with salt. She tightens her grip. Again—

Slower now, her strength wavering, she is on rhythm with the clock. As the pendulum sways, the blade rises and falls again.

Again. Again. Again.

Again.

Exhausted, her body goes limp and falls to the floor. The knife clatters on the tile nearby. Her eyes are still closed and soaked with tears. They are tears of sadness, happiness, anger and redemption. A weight has been lifted, a sentence pardoned. She is free.

“OH, GOD!”

It is a man’s voice. His voice, agonized but still very much alive.

Her eyes snap open. She is on the floor, the knife nearby, but the dining room is immaculate white. No blood. No slaughtered body. Her husband is still seated at the table, entirely unharmed, massaging his temples. The newspaper has been discarded, at least, and he appears to be distressed about something.

“WILL IT EVER STOP?” he screams, pounding a fist against the table.

There is not a scratch on him. How is this possible?

“I’ve repented,” he continues, whispering now. “I’ve changed.”

Tears leak down his face. He cups his forehead in his palm. “I went too far. It was a terrible, evil thing. But I’m sorry. I’M SORRY!” he yells the final apology to the room and slumps into the chair. It is clear that he is tormented, but by what? The knife has failed. He is still alive.

She crawls to her knees, picks up the knife and inches toward his thigh beneath the table. With a quick plunge, she stabs it into his leg. She can feel the exquisite sensation of metal piercing skin, muscle and ligaments ripping, but the blade itself vanishes into a mist when it touches him. No blood, only vapor. Still, he winces in reaction.

“Get out of my head!” he howls, crying fully now. Into his hands. Blubbery and pathetic.

The grandfather clock drones on. There is an uncanny feeling of déjà vu and sense that her time is running out. She stabs his leg one more time. He yells again, not hurt physically but mentally.

“Please,” he whimpers, almost inaudible. “Please—stop.”

A haze settles over the room. It is as if she is watching the scene from afar. He is still sobbing in the chair and she is somehow floating away. She can feel her mind start to loosen, to tire. Images blur, leaving only vague traces of grey and black streaks. The incessant ticking of the clock amplifies, reverberates. Time feels ambiguous. Do the ticking noises represent seconds or minutes, hours or days?

There is so much mist. Her body seems to be part of it, mixing with the moisture, evaporating. Unconsciousness is everywhere.

~ ~ ~

When her mind returns it is another day, another loop. She is standing in the kitchen, preparing a new recipe from an old book. How curious, she thinks, that there is already a pot of boiling water on the stove. She must have prepared it earlier and forgot.

And where did that pie come from? What does it mean?

No time to worry. There is much to do before the clock strikes six.

*

Like this story? Support the author by reviewing it on Amazon and Goodreads.

Don’t miss the latest SpookyBooky content! Follow us on social media: