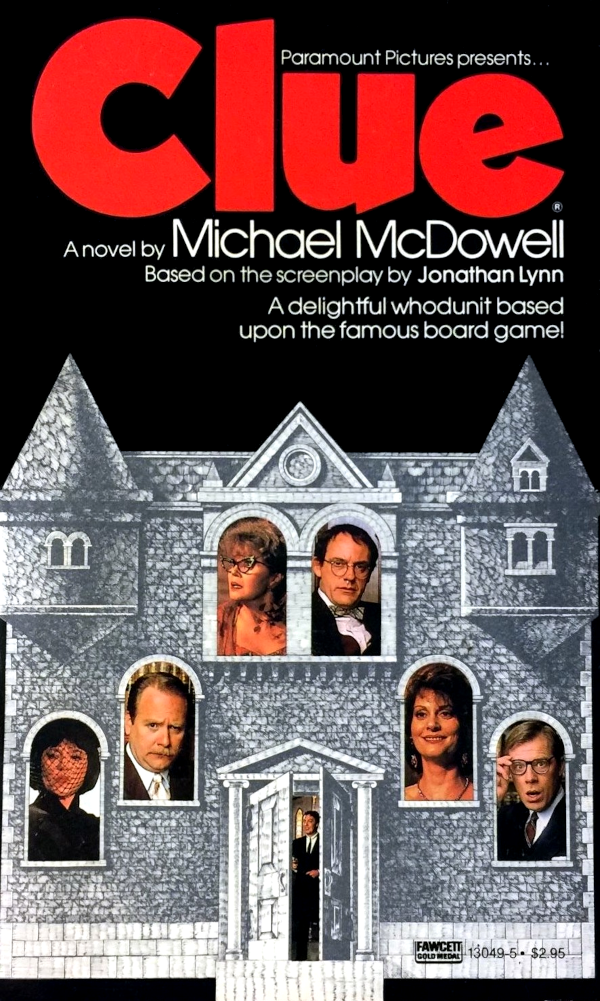

Movie novelizations rarely possess literary merit, and yet it’s common to see them sell at high prices on eBay. The Clue novelization by Michael McDowell (1950-1999) is particularly pricy, with bidding wars often exceeding $150. The high demand is likely a combination of the film’s enduring legacy and curiosity to see what a horror master like McDowell would do with a novelization. Add in the scarcity of supply and I understand why fans are constantly seeking it out. I certainly was.

When I at last got my hands on a copy, I decided to not just read it but literally transcribe every word. The archivist in me felt it was important to save a digital copy should the book ever disappear completely to the dusty shelves of rare book collectors. This transcription process was one of my most cherished reading experiences. There are few ways to be more intimate with a book than to retype every word. It requires slower reading and allows for discovery of technique you would not normally notice, such as stylized word repetition, clever usage of punctuation, and white space.

I knew McDowell was a genius going in, but “reading” the novel this way made it easier to see why. His attention to body language, minor shifts in mood, atmospheric characters, implied and overt sexuality are all skills which make his original novels dazzle, and made him perfect for this project. If ever there was a novelization with literary merit, this is it.

Content-wise, there’s no deviation from the film’s script and yet it is still a brand new experience to essentially re-watch every frame through McDowell’s superb narration. Consider, for example, this delicious description of Yvette:

Yvette was the nec plus ultra of downstairs maids. She was young. She was astonishingly beautiful. She had better curves than a major league pitcher. She was dusting the books in the library with a feather duster that wasn’t half as soft as the waves of her lustrous hair. Yvette was not only a French maid; she was a fetishist’s dream of a French maid, and she had an outfit to match: a glossy black dress, cut high on the thigh and low in the bosom, so tight it whined when she walked. A starched white cap was perched absurdly atop her head, and a starched white apron was slung low across her waist, like a remembrance of chastity. Her stockings were at once black and sheer, and the seam that ran along the back of her calf was a draftman’s ecstasy of curve. Her shoes were high in the heel and tight in the toe, completing a figure that was—all in all—at once startling, grotesque, and divine.

This Yvette description deserves to be framed and hung in a museum, but it’s far from the only time McDowell shows off his prose prowess. Wit is peppered throughout, giving familiar scenes a whole new level of humor. He amplifies subtext to outlandish proportions and delivers a constant bonanza of fabulous word choice. When not riotously funny, he’s awe-inducing. The opening paragraphs are such an exquisite depiction of a gloomy, gothic mansion, that it rivals Shirley Jackson:

It was the kind of house you always see from the road, never up close. Seen through vast gates, at the end of a winding gravel driveway, half-hidden by the foliage of trees planted more than a half century ago. You slow down as you pass it, trying to catch glimpses over the vine-covered brick walls that surround it, of its peaked gables and its dark windows and curious porches. It is silent and secret.

You use your imagination and try to think who might live there: a rich woman, the flickering ember of a family the world thought had died out decades before 1954. A reclusive millionaire with a passion for diet soft drinks and some silent film star long since passed. A gangster, ensconced with cronies over cribbage, and a bored, peroxided doxy who knocks about from room to room in the silent, empty house.

But even as you make these romantic conjectures, you know that you’re wrong, and the truth—whatever it might be—of the house and what transpires within is much stranger than anything you can imagine. The brick wall turns, but the road you’re traveling on curves in another direction. You drive on, and perhaps in the rear-view mirror you catch a glimpse of a finger of chimney above the massive trees that surround the house, and that is all.

Houses like that keep their secrets from people like you and me.

Outside of jaw-dropping lines such as these, the book has another big attraction—an extra ending not included in the film. Fans know there is not one answer to whodunit, but three. At home you can decide to play all three endings or watch one at random. The book includes these possibilities, but also features a fourth ending scrapped from the screenplay. It’s an absurd, preposterous ending and I’m not surprised it was discarded, but I have to say it’s also one of the most fun. I won’t give specifics out of respect for those who might want to hunt down a copy, but if you’re desperate to find out there is a summary on Wikipedia.

Overall, while this book is nearly a line-for-line replica of the iconic film, McDowell’s talented way with words adds next-level charm even if you’ve watched the movie a hundred times. McDowell notices little quirks and clues in the characters that I never picked up on, and he even offers subtle jabs at some of the more campy moments. It’s a shame this novelization will likely never be re-printed and is so difficult to find, because it is a raucous ride from beginning to end and a wonderful companion to a great film.

Thanks for reading! Follow for more reviews of the obscure and unusual…